M. HENRY JONES

M. Henry Jones arrived in New York from Buffalo in 1975 with a scholarship to the School of Visual Arts and a compulsive fascination with animation.

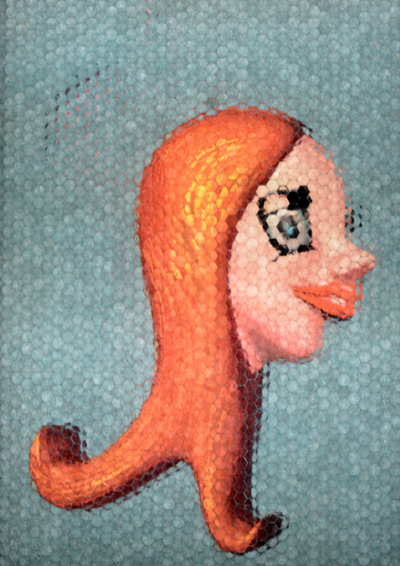

Jones’ childhood preoccupation with animation was followed by a broader exploration of techniques employed to create images, beginning with those that budded between the coming of photography and the birth of the movies, like the zoetrope, the praxinoscope, the kinetoscope, and moving on to later developments, such as lenticular photography and holograms. Most recently Jones has been using Fly’s Eye lenses to make 3-D portraits. (On exhibit) Jones has always combined his tech infatuation with cartoon images, executed in his own manner, which is neither superhero-based in the classic American manner, nor does it have the look beloved of most Brit practitioners of Comic Style, which is that of a truculent adolescent.

As of now, moving images and 3D are his principal obsession. He continues to work with lenticular photography but is moving increasingly on to the Fly's Eye lens, which he sees as a logical extension of the delight he found early in animation. “I think the Fly's Eye photography that I'm doing now is kind of a heightened manifestation of that." Fly's Eye 3-D integral photography allows anyone to see 3-D pictures without the use of glasses or VR hood. 2,644 individual photographs come together into one summation image in order to give the viewer a 3-D experience. This technology imitates aspects of the image recognition of a dragon fly. The technique involves fragmenting visual reality in order to reconstruct it in a different place. Electronic data is processed and re-integrated photographically under an optical lens array. M. Henry Jones and his team developed this computer-assisted optical technology to advance the art & science of photography. The remarkable dynamic affect has to be seen in person.

Jones' was included in MoMA's Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983 exhibit from Oct 2017-April 2019. 'Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983 is the first major exhibition to fully examine the scene-changing, interdisciplinary life of this seminal downtown New York alternative space. The exhibition tapped into the legacy of Club 57’s founding curatorial staff—film programmers Susan Hannaford and Tom Scully, exhibition organizer Keith Haring, and performance curator Ann Magnuson—to examine how the convergence of film, video, performance, art, and curatorship in the club environment of New York in the 1970s and 1980s became a model for a new spirit of interdisciplinary endeavor. Responding to the broad range of programming at Club 57, the exhibition presents their accomplishments across a range of disciplines—from film, video, performance, and theater to photography, painting, drawing, printmaking, collage, zines, fashion design, and curating. Building on extensive research and oral history, the exhibition features many works that have not been exhibited publicly since the 1980s.'

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ArtUSlaFPt0

http://press.moma.org/2016/11/club-57/

Jones’ childhood preoccupation with animation was followed by a broader exploration of techniques employed to create images, beginning with those that budded between the coming of photography and the birth of the movies, like the zoetrope, the praxinoscope, the kinetoscope, and moving on to later developments, such as lenticular photography and holograms. Most recently Jones has been using Fly’s Eye lenses to make 3-D portraits. (On exhibit) Jones has always combined his tech infatuation with cartoon images, executed in his own manner, which is neither superhero-based in the classic American manner, nor does it have the look beloved of most Brit practitioners of Comic Style, which is that of a truculent adolescent.

As of now, moving images and 3D are his principal obsession. He continues to work with lenticular photography but is moving increasingly on to the Fly's Eye lens, which he sees as a logical extension of the delight he found early in animation. “I think the Fly's Eye photography that I'm doing now is kind of a heightened manifestation of that." Fly's Eye 3-D integral photography allows anyone to see 3-D pictures without the use of glasses or VR hood. 2,644 individual photographs come together into one summation image in order to give the viewer a 3-D experience. This technology imitates aspects of the image recognition of a dragon fly. The technique involves fragmenting visual reality in order to reconstruct it in a different place. Electronic data is processed and re-integrated photographically under an optical lens array. M. Henry Jones and his team developed this computer-assisted optical technology to advance the art & science of photography. The remarkable dynamic affect has to be seen in person.

Jones' was included in MoMA's Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983 exhibit from Oct 2017-April 2019. 'Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983 is the first major exhibition to fully examine the scene-changing, interdisciplinary life of this seminal downtown New York alternative space. The exhibition tapped into the legacy of Club 57’s founding curatorial staff—film programmers Susan Hannaford and Tom Scully, exhibition organizer Keith Haring, and performance curator Ann Magnuson—to examine how the convergence of film, video, performance, art, and curatorship in the club environment of New York in the 1970s and 1980s became a model for a new spirit of interdisciplinary endeavor. Responding to the broad range of programming at Club 57, the exhibition presents their accomplishments across a range of disciplines—from film, video, performance, and theater to photography, painting, drawing, printmaking, collage, zines, fashion design, and curating. Building on extensive research and oral history, the exhibition features many works that have not been exhibited publicly since the 1980s.'

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ArtUSlaFPt0

http://press.moma.org/2016/11/club-57/

|

|

|

|

ArtNet Review: Anthony Haden-Guest on Garner Arts Center’s Stroke of Genius.

It's a combination of obsessiveness and sheer peculiarity.

February 25th 2016 (Excerpt)

The upper floor of the 8,000 square-foot space is occupied by Pushing the Optical Envelope, the defining subtitle of Jones’s work. Jones—he is politely insistent on the M—is an artist/inventor/tinkerer in his 50s who grew up in Buffalo, and worked at Artpark, the outdoor arts festival, in his teens. Artists whose projects left a lasting imprint included Gordon Matta-Clark, who sheared a building into nine segments with a power saw, Laurie Anderson, dueting with a playback tape on an electric violin, and Dennis Oppenheim, who impressed giant thumbprints on a parking lot.

His future direction determined, Jones came to Manhattan in 1975 with a scholarship to the School of Visual Arts, where fellow students with whom he became friendly included Peter Zaremba, front man of the Garage Rock band, the Fleshtones. Jones’s first New York animation was a self-portrait, assembled from still photographs, which shows him crossing a road. It was Zaremba who suggested a more ambitious project: an animation of a Fleshtones performance of a Lou Reed song, Soul City. Soul City is one of those special handiworks—like the Chrysler Airflow automobile of 1934—which can be said to occupy a niche in art, design and tech history too. Jones made this 2 1/2 minute animation by hand-cutting 1,700 individual photographs with an X-Acto knife, adding color to each, and reshooting the segments frame by frame against a constantly changing background.

Just three years later, of course, this Analog Age hard labor would be rendered obsolete by the coming of MTV and a decade later it was, Hello, Photoshop! That said, Jurassic technology, first human efforts to solve a problem, have a special look. 19th Century ironwork, the first space modules, early Ferraris and Bugattis are not ridiculous compared to their sleek progeny, just different. So with for Soul City. The takeaway is that Jones’s arduously made cut-outs have now been swallowed up into that ever-hungrier ecosystem: The Art World.

Pushing the Optical Envelope, is at once folksy and hi-tech, unpushily ambitious. Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia would have blessed it, I imagine, and Rube Goldberg too. Jones’s childhood preoccupation with animation was followed by a broader exploration of techniques employed to create images, beginning with those that budded between the coming of photography and the birth of the movies, like the zoetrope, the praxinoscope, the kinetoscope, and moving on to later developments, such as lenticular photography and holograms. Most recently Jones has been using Fly’s Eye lenses to make 3-D portraits.

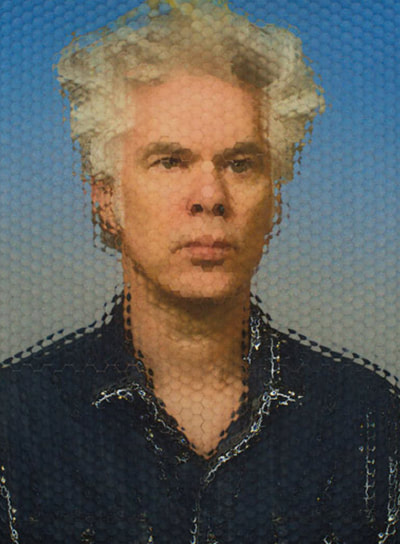

Here in Garnerville are early defining pieces, like Soul City, and such fruits of his more recent activity as 3-D portraits of Jim Jarmusch, Robert Frank, June Leaf, and Boonsri Dickinson who, back in Jones’s place on East 9th Street, introduced me to that techie supernova—both in intensity and duration—Google Glass. Here too are Jones’s giant wheels, which focus the eye on a single image. These are usually drawn by Jones himself in a cartoon-like manner which is wholly his own, and does not reference the increasingly mundane vocabulary of superhero graphics. The content can seem dark. On one of wheels a pig morphs into an alien, which turns into a girl, Molly, who turns into a duck, and so back into a pig.

There are also sculptures cast in resin of favorite Jones characters, like Snakemonkey, and Slatherpuss, a creature he encountered in a long ago dream, name and all, and who has wings, protuberant eyes and an orange beak. Or Killer Baby, an animated sculpture he created on a stroboscopic zoetrope. This is a representation of an infant, wielding a knife, and apparently yowling, who is viewed on a black hooded screen. But the world of Henry Jones is not creepy. He is a sweet-natured fellow, indeed abnormally so, and his work doesn’t have that slight resonance of the sinister you can even pick up from most cartoony art, even Disney. What it does have is a combination of obsessiveness, sheer peculiarity and an appetite for work that suggests a touch of that over-used word, genius.

Garnerville is just 45 minutes from Manhattan, and the culture which has nourished Jones was well represented. Frankie Infante, the guitarist with Blondie was there, as were Leonard Abrams, formerly the publisher of the East Village Eye, Keith Patchell, the composer, Esther Regelson, who wore the animation camera, and the poet/performer, Gabriel Don. Also Marc Miller, a notable dealer in ephemera from that culture, and others, and Mark Brady, a cinematographer on What About Me? Likewise Maria del Greco, the photographer, and Margaret Bazura, who worked with the Rivington School, and created the virtual reality experience for the show. Peter Zaremba sang, and he was backed on the guitar by another of the Fleshtones, Keith Streng.

It's a combination of obsessiveness and sheer peculiarity.

February 25th 2016 (Excerpt)

The upper floor of the 8,000 square-foot space is occupied by Pushing the Optical Envelope, the defining subtitle of Jones’s work. Jones—he is politely insistent on the M—is an artist/inventor/tinkerer in his 50s who grew up in Buffalo, and worked at Artpark, the outdoor arts festival, in his teens. Artists whose projects left a lasting imprint included Gordon Matta-Clark, who sheared a building into nine segments with a power saw, Laurie Anderson, dueting with a playback tape on an electric violin, and Dennis Oppenheim, who impressed giant thumbprints on a parking lot.

His future direction determined, Jones came to Manhattan in 1975 with a scholarship to the School of Visual Arts, where fellow students with whom he became friendly included Peter Zaremba, front man of the Garage Rock band, the Fleshtones. Jones’s first New York animation was a self-portrait, assembled from still photographs, which shows him crossing a road. It was Zaremba who suggested a more ambitious project: an animation of a Fleshtones performance of a Lou Reed song, Soul City. Soul City is one of those special handiworks—like the Chrysler Airflow automobile of 1934—which can be said to occupy a niche in art, design and tech history too. Jones made this 2 1/2 minute animation by hand-cutting 1,700 individual photographs with an X-Acto knife, adding color to each, and reshooting the segments frame by frame against a constantly changing background.

Just three years later, of course, this Analog Age hard labor would be rendered obsolete by the coming of MTV and a decade later it was, Hello, Photoshop! That said, Jurassic technology, first human efforts to solve a problem, have a special look. 19th Century ironwork, the first space modules, early Ferraris and Bugattis are not ridiculous compared to their sleek progeny, just different. So with for Soul City. The takeaway is that Jones’s arduously made cut-outs have now been swallowed up into that ever-hungrier ecosystem: The Art World.

Pushing the Optical Envelope, is at once folksy and hi-tech, unpushily ambitious. Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia would have blessed it, I imagine, and Rube Goldberg too. Jones’s childhood preoccupation with animation was followed by a broader exploration of techniques employed to create images, beginning with those that budded between the coming of photography and the birth of the movies, like the zoetrope, the praxinoscope, the kinetoscope, and moving on to later developments, such as lenticular photography and holograms. Most recently Jones has been using Fly’s Eye lenses to make 3-D portraits.

Here in Garnerville are early defining pieces, like Soul City, and such fruits of his more recent activity as 3-D portraits of Jim Jarmusch, Robert Frank, June Leaf, and Boonsri Dickinson who, back in Jones’s place on East 9th Street, introduced me to that techie supernova—both in intensity and duration—Google Glass. Here too are Jones’s giant wheels, which focus the eye on a single image. These are usually drawn by Jones himself in a cartoon-like manner which is wholly his own, and does not reference the increasingly mundane vocabulary of superhero graphics. The content can seem dark. On one of wheels a pig morphs into an alien, which turns into a girl, Molly, who turns into a duck, and so back into a pig.

There are also sculptures cast in resin of favorite Jones characters, like Snakemonkey, and Slatherpuss, a creature he encountered in a long ago dream, name and all, and who has wings, protuberant eyes and an orange beak. Or Killer Baby, an animated sculpture he created on a stroboscopic zoetrope. This is a representation of an infant, wielding a knife, and apparently yowling, who is viewed on a black hooded screen. But the world of Henry Jones is not creepy. He is a sweet-natured fellow, indeed abnormally so, and his work doesn’t have that slight resonance of the sinister you can even pick up from most cartoony art, even Disney. What it does have is a combination of obsessiveness, sheer peculiarity and an appetite for work that suggests a touch of that over-used word, genius.

Garnerville is just 45 minutes from Manhattan, and the culture which has nourished Jones was well represented. Frankie Infante, the guitarist with Blondie was there, as were Leonard Abrams, formerly the publisher of the East Village Eye, Keith Patchell, the composer, Esther Regelson, who wore the animation camera, and the poet/performer, Gabriel Don. Also Marc Miller, a notable dealer in ephemera from that culture, and others, and Mark Brady, a cinematographer on What About Me? Likewise Maria del Greco, the photographer, and Margaret Bazura, who worked with the Rivington School, and created the virtual reality experience for the show. Peter Zaremba sang, and he was backed on the guitar by another of the Fleshtones, Keith Streng.